Crossing the bay

I turned 40 this year, and next thing I knew, I was heading over to Marin County for botox.

To get there from Alameda, I've been driving over the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. It's the dreamiest of the bay crossings —the green peaks peaks of Marin, the red rock of Red Rock Island, the partially-post-industrial coastline of Richmond, glimpses of The City — and also the site of one of the Bay Area's more visible fights between motorists and cyclists.

For my first appointment in Marin, I had to drive at the peak of the morning rush. As I inched forward my car along I-580 through Richmond and then over the bluff toward the bridge, I watched the clock count down toward my appointment time. I had waited months for this appointment and didn't want to be late. I had called in a favor from grandparents to take my kids to their schools that morning, but apparently even giving myself an hour an a half wasn't going to be sufficient. As I sat in my car, I could feel my jaw clench and my allegiances shift from "team cyclist" to "team motorist."

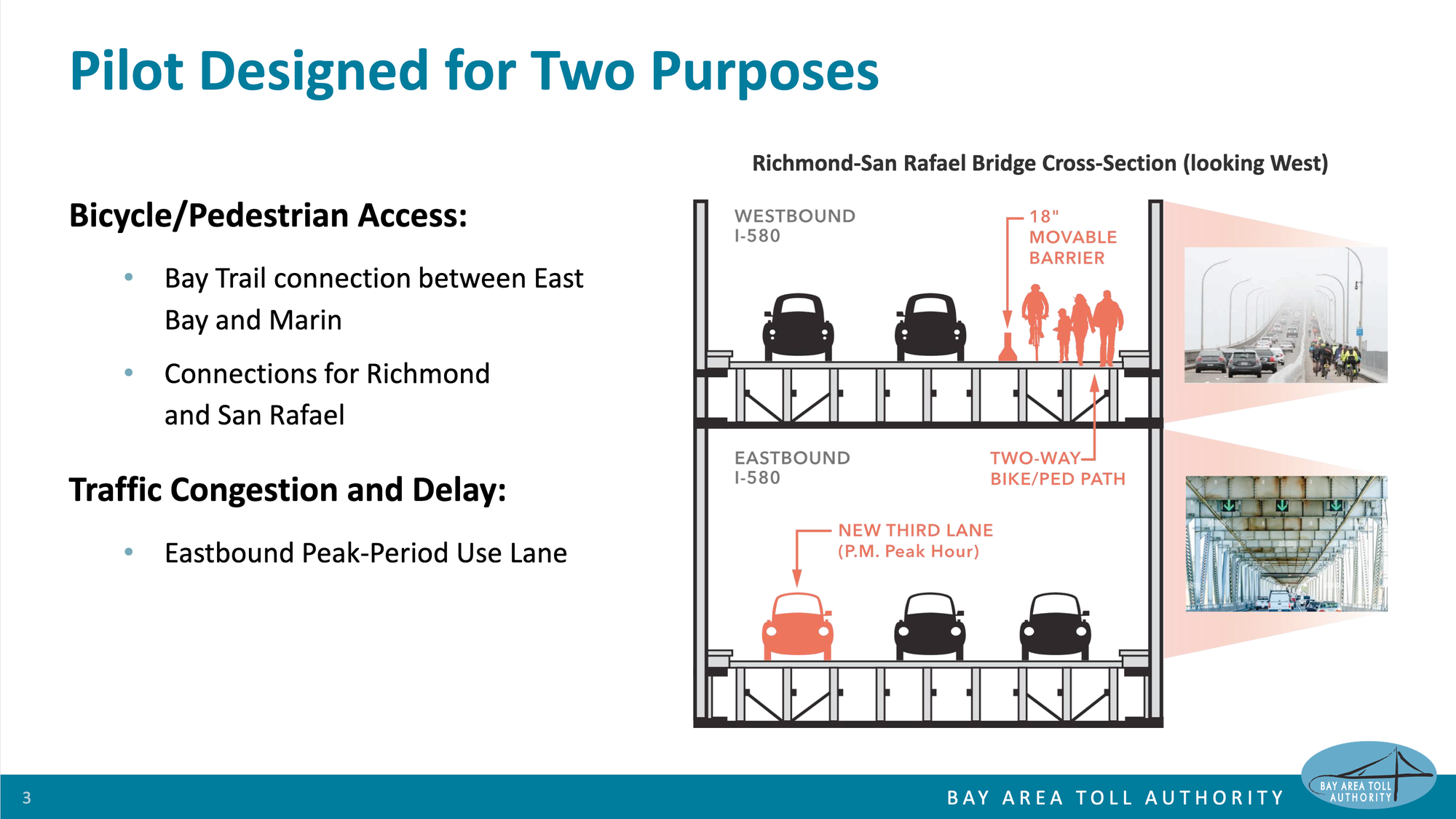

The bridge has width for three lanes on its upper deck. Two of these are for motorists driving westbound toward Marin. Since 2019, the third has been separated by temporary barriers to serve as a protected path for cyclists and pedestrians.

I've loved and supported this pilot of a bay crossing designed for cyclists and pedestrians — and yet there I was, sitting in my car alongside other cars and trucks headed to Marin, just wishing I could drive in that darn third lane.

What planners can tell us when we give them time

Last week, a regional body called the Bay Area Toll Authority ("BATA") Oversight Committee met to review the allocation of lanes on the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge and to consider the future of that pilot program.

The slide-deck of 15 slides that staff planners prepared for the BATA meeting are extremely impressive in their depth, breadth, and clarity. For every question, there is an analysis and an answer — both for questions that a decision-maker could ask in good faith and for questions that someone who had already made up their mind could ask in bad faith.

I'm so impressed with this slide-deck because it provides an example of what planners can tell us when we give them time (and money to pay for their time).

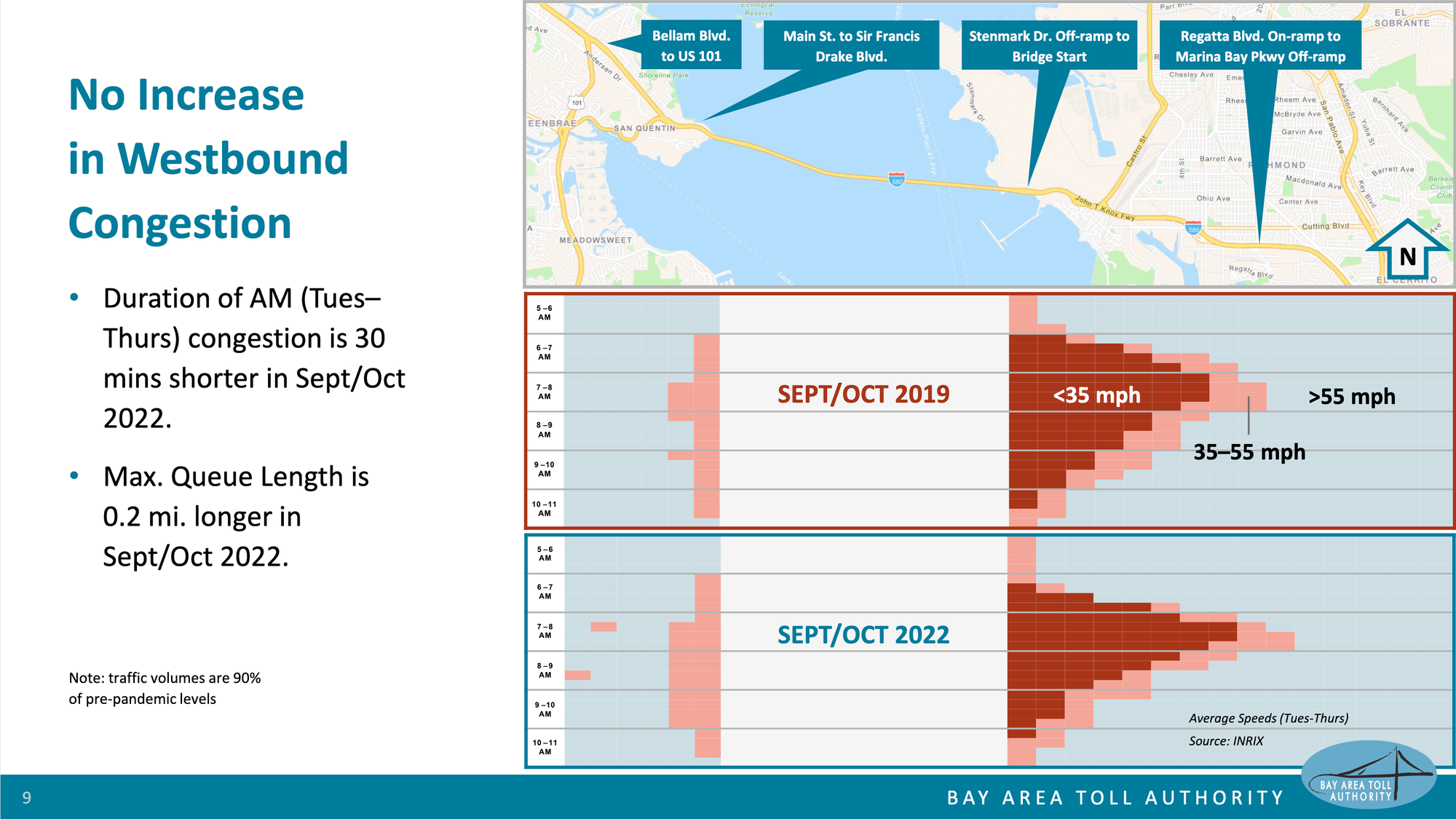

First, to my question/complaint as I sat in traffic that morning, the planners find that westbound auto traffic is roughly similar to before the bike/ped pilot. This analysis is based on data collected by Inrix (from individual drivers' smartphones and fleet vehicles' GPS units):

My experience was rough — but it would have been similarly rough in 2019.

An important detail I didn't mention earlier: before 2019, the bike/ped lane was a "breakdown" lane for autos. There have never been 3 lanes for westbound auto traffic. This analysis supports the conclusion that the bike/ped lane itself hasn't further worsened auto traffic.

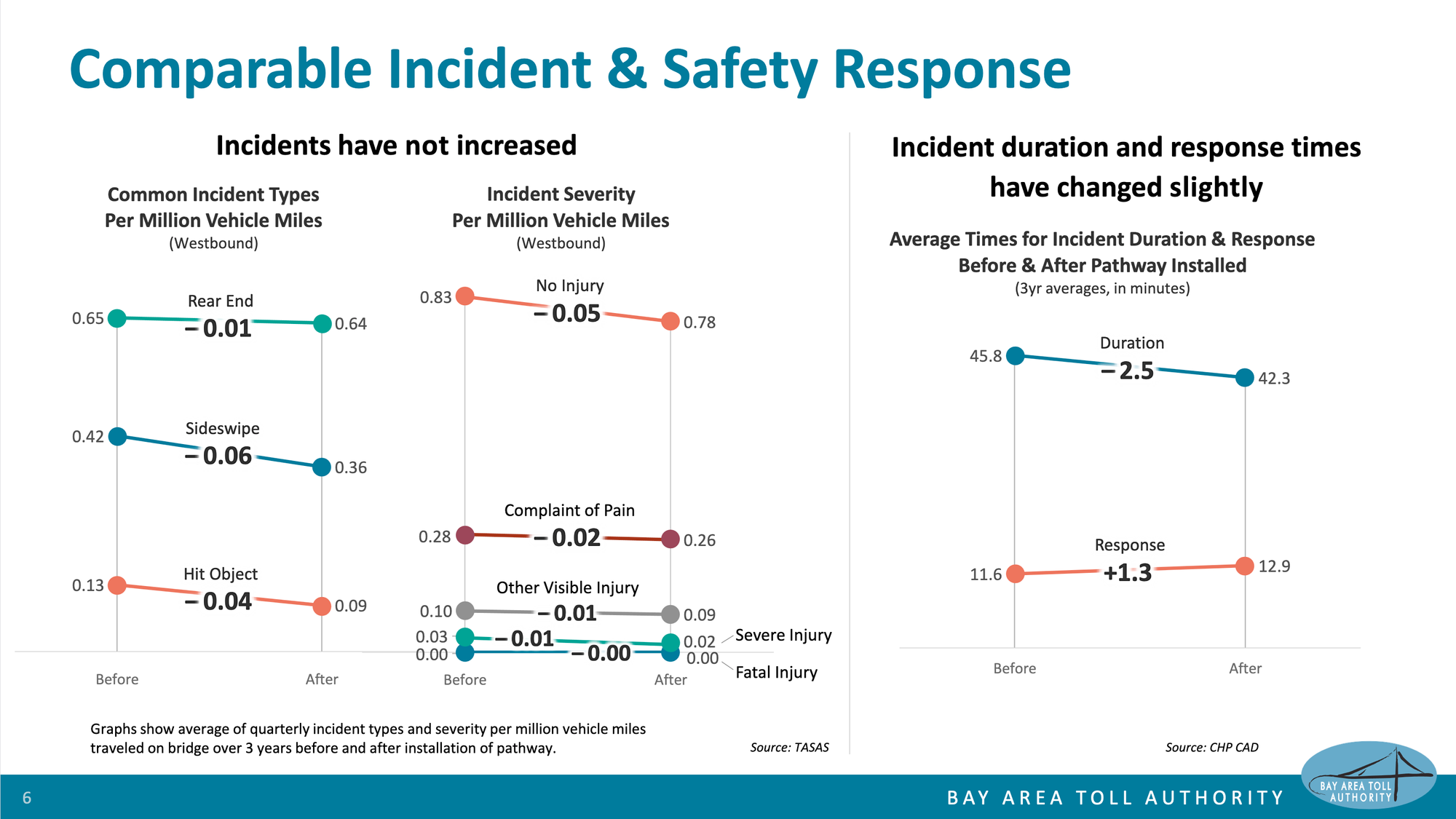

But what about effects of removing the "breakdown" lane? The planners have an analysis for that, too, which indicates no significant changes in incidents or delays in response:

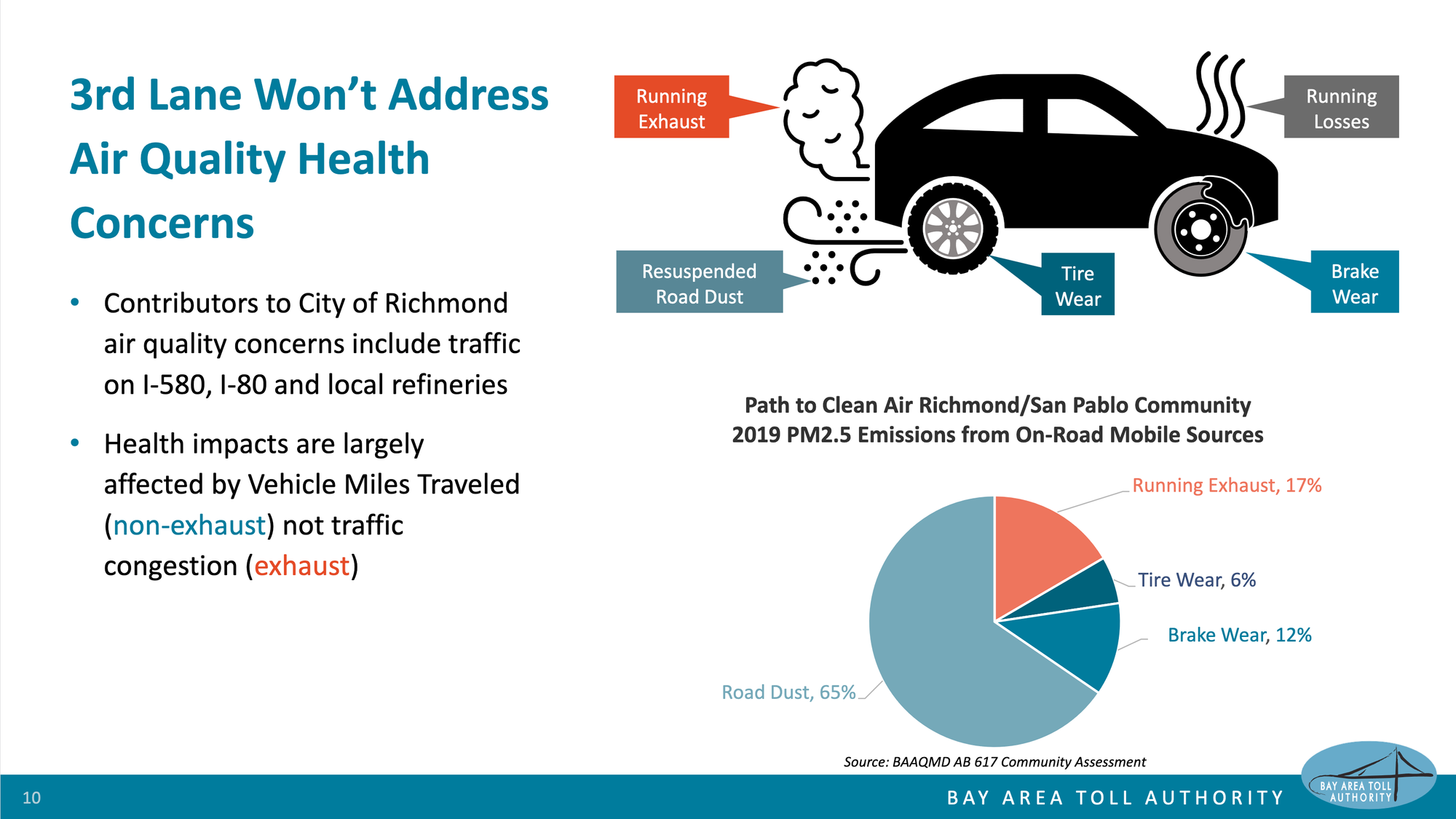

O.K., O.K. some may respond to this information. The bike lane may not be causing issues on the bridge. It may be nice for wealthy cyclists, but isn't it creating more pollution for poorer residents of Richmond? To this sort of question (which some ask genuinely; and others may not), the planners also have relevant data:

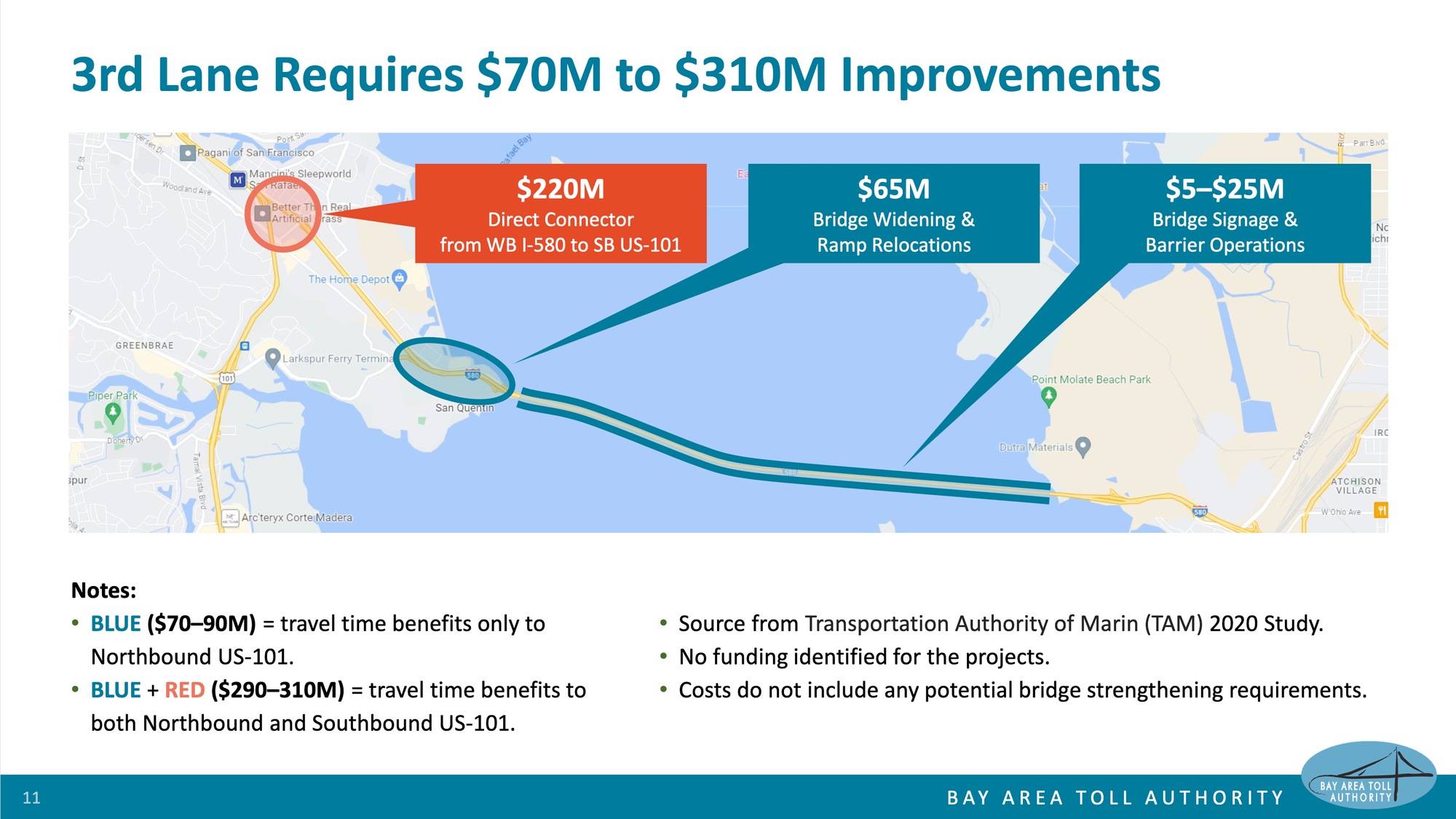

Finally, for any decision-makers that are still interested in converting the former "breakdown" lane and current bike/bed lane into a real third lane for auto traffic, the planners have actually considered the engineering work that would be required:

This is one of the most impressive aspects of this presentation: the planners are both equipped with thorough analysis of current conditions and engineering estimates for a complete series of potential future changes. This means that decision-makers can't ask for something without also understanding its costs and its limitations.

Note how the slide provides separate costs for making improvements to improve I-580 to northbound US-101 and I-580 to southbound US-101. In my first appointment with the orofacial pain specialist in San Rafael, I drove to northbound 101; in my most recent visit to the oral surgeon in Corte Madera, I drove to southbound 101 and noticed how that connection currently requires driving along surface streets.

By having both estimates, the planners make it clear to decision-makers that if their goal is to decrease westbound auto travel time at peak hours, then they can't just re-allocate the third lane to auto traffic. That would just shift an existing choke point. They would also have to commit to what are likely hundreds of millions of dollars of additional construction.

The planners are hinting that by making it quicker to drive across the bridge at peak times, then even more people will decide to do so. The overall number of "vehicle miles traveled" will increase — and negative side effects that are associated with more people driving more miles will increase.

Planners refer to this as induced demand. It's one aspect that I think deserved to be unpacked and given its own slide.

Equipped with all this information, the BATA Advisory Committee approved the planners' recommendations to:

- retain the existing pilot arrangements with the bike/ped lane on the upper deck of the bridge

- retain the pilot arrangements for eastbound auto lanes on the lower deck of the bridge (which I have not discussed in this blog post)

- commission further study by a transportation research group at UC Berkeley

- make a decision for permanent use of the lanes by the end of 2024

What this means for Alameda

The future Richmond-San Rafael Bridge may not be specifically relevant to Alameda but the patterns and pitfalls of decision-making that BATA/MTC's planners are addressing with this presentation are all too relevant to Alameda.

The level of preparation and detail in these slides is relevant for politicians like Alameda's Trish Herrera Spencer and Tony Daysog.

Vice Mayor Daysog is often for something until he's against it. He'll speak to Alameda's overall positive aspiration values — and then vote against pursuing those values when the budget to implement those values is presented. As a politician, is he against change or is he just against spending money? Probably both. However, he can maintain some deniability when decision-making on an important project is spread out over multiple votes. So I think of how MTC/BATA's planners included full cost estimates in this presentation — that looks like an effective way to handle a politician who might want to vote to re-allocate the third lane away from cyclists but not want to follow through with the full implementation cost to actually realize the full value for drivers.

Note that my goal with these comments isn't to suggest that specific planning processes or presentations will change the minds and the votes of specific politicians. My goal is to suggest that presenting sufficiently detailed plans that include dollar amounts sooner rather than later limits the ways that decision-makers can try to have it both ways — to try to be for something when it's a concept and against it when it's a cost.

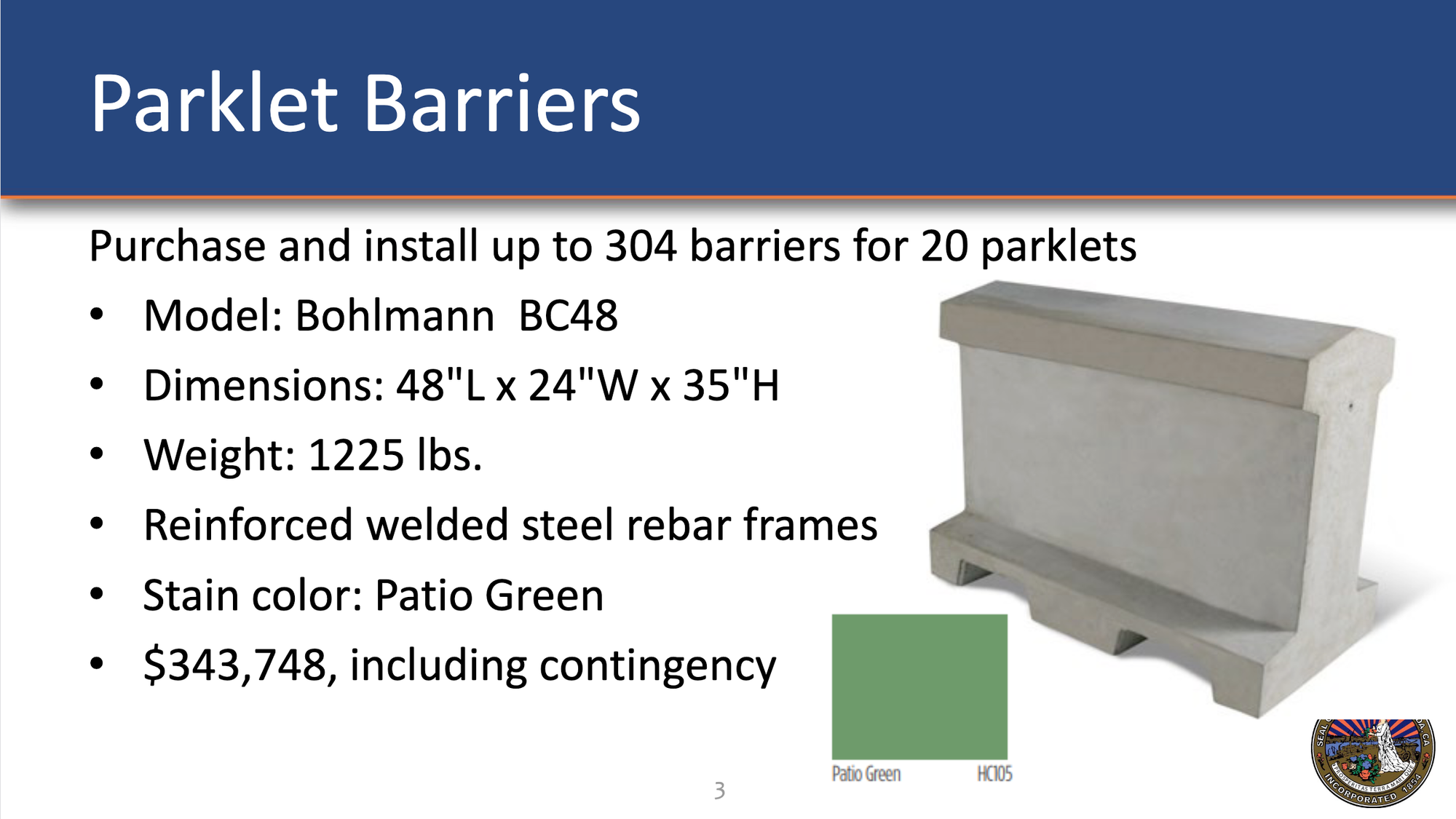

Councilmember Herrera Spencer opposes change by digging deep. At last Tuesday's City Council meeting she didn't argue against parklets and bike lanes of the core areas of Park Street and a limited stretch of Webster Street (a plan that has been in progress for years and that I've blogged about previously). Instead, she argued, in her words, for safety by repeatedly questioning staff about the concrete barriers they proposed purchasing to surround existing parklets to protect them from motorists: for what exact auto speeds are these barriers rated to protect against? why were staff proposing to purchase concrete barriers of this short length rather than standard "K-rail" that is 20 feet in length? why didn't staff selected a concrete barrier that is rated for use on the California State Highway System? These latest questions were in addition to her questions at past City Council meetings about MUTCD regulations and about whether all the plan documents had been signed and stamped by a Professional Engineer. When staff weren't equipped specific answers for each and every one of these questions — even if the question was not actually relevant to the matter at hand — she accomplished her goals: casting doubt on the overall project, while appearing to be a responsible elected official.

As with my comment on providing budget estimates sooner rather than later, presenting implementation details isn't about changing the minds of an elected leader — it's about helping to focus electeds' discussion on the key questions at hand and de-incentivizing grandstanding and whataboutism.

That said, in the case of the Park/Webster project, Alameda city staff did in fact have a slide prepared about the specific concrete barriers. If the slide had included information on their exact speed rating, would Councilmember Herrera Spencer have been satisfied? Or would she have just come up with a different unaddressed detail to quibble over?

That slide does also include an exact budget for buying the barriers (as this agenda item was specifically to request approval for the purchase). The slide-deck did not articulate and cost out other longer-term options. When public commenters and Councilmembers asked about the potential cost to move Park and Webster's curb — to permanently extend the sidewalk and narrow the roadway — staff accurately described that as a much more expensive project. (Moving curbs also necessitates re-doing drainage and other utilities, which can be quite expensive.) However, staff were not equipped with a budget estimate. Without even an estimate of an order of magnitude cost, the debate momentarily entertained the possibility of deferring on the short-term incremental progress to wait for a long-term solution — a long-term solution that some of those same public commenters and Councilmembers will just oppose when the price tag is attached to it.

Councilmember Herrera Spencer also argued that bike lanes and parklets on Park and Webster impede the city's first responders. Staff and other Councilmembers could refer second-hand to Alameda Fire Department's involvement and approval of the plans. But a slide like the one in the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge slide-deck could have been useful to visualize how incidence responses have not been impacted in a significant or meaningful manner.

I'm probably wishing for the impossible here: that city staff will have enough time (and resources) to prepare plans and analyses that address all lines of argument (both probing questions asked in good-faith and questions asked out of a strategy to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt). That they'll be able to speak to all these competing concerns within a five minute slot on a Tuesday night at 10 p.m. or 11 p.m. or maybe even midnight. I'm also wishing for the impossible in that carefully and thoroughly prepared presentations by planning staff will foster similarly methodical and thoughtful decision-making by all elected officials — even ones I disagree with. Still, there's value in considering what planners can tell us when we give them sufficient time and sufficient resources.

To close out my story, I've found that when I've been able to schedule my appointments at any time other than the immediate start of the workday, then auto traffic over the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge moves quite quickly (just as the Intrix speed measurements indicated). It's a pleasurable drive, as the bridge rolls up and down, and a fabulous view. I look forward to trying the trip across the bridge again, when I'm hopefully no longer needing to go to any more of these dental specialists, on my e-bike.

November 15, 2023: After sleeping on this blog post, I firmed up the conclusion and also adding in an aside about land-use in Marin.