An ongoing argument of this blog is that to meet Alameda's adopted goals for traffic safety and for climate change, the city's staff and consultants need to be on the forefront of street designs.

Building a "safe" bike lane to the engineering standards of 20 years ago is no longer actually safe. In part, this is due to changes like the increase in vehicle sizes and the decrease in our care for our fellow Americas — changes that have increased the actual rate of injuries and deaths. In part, those "traditional" unprotected bike lanes were never actually safe for kids or seniors — it's just that our definition of who can be a cyclist have finally caught up from the days when transportation scholars held debates about "vehicular cyclists" — and now we can perceive and discuss many more ways in which our transportation network is inaccessible to everyone from kids to seniors to people of all ability levels who want to safely and comfortable get somewhere.

Some advocates try to argue against the entire traffic engineering profession. My worldview was shaped in part by James Howard Kunstler's writing on American auto-centric development. (Last I checked, he's gone on to be a "contrarian" on COVID vaccines and to hawk schemes related to gold.) But while I was a teenager reading Kunstler on the clusterf*ck of American traffic engineering in the late '90s, I now have a different viewpoint — and the professional practices of engineering and planning are in different (and better) places.

Send Alameda transportation staffers to Miami

Instead of firing all the city's traffic engineers and planners, I believe the city should be sending them all on an all-expense-paid trip to Miami.

Seriously.

Miami was the host city for last week's Designing Cities conference put on by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). It's an annual event and an organization focused on improving professional practices and improving outcomes on the ground — particularly for pedestrians, cyclists, and the riders and operators of transit — but also for individual drivers and professional logistics drivers.

A key word in the organization's name is "city." NACTO focuses on professional practices, policies, and design standards for transportation networks within cities.

This is an intentional contrast with an orientation that has defined American transportation engineering for many decades: standards intentionally at the state and federal level for the Interstate Highway System and for state highways — with little regard for how those standards also apply within urban downtowns, dense neighborhoods of mixed uses, or in any area "off the highway."

Moving people and goods between metro regions along "limited access" highways was the primary goal — moving people or goods within cities, neighborhoods, and along ordinary "surface" streets was an afterthought.

The Other "Green Book"

The standards for all those highways has been controlled for decades by a private non-profit organization called the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). In the words of Wikipedia:

While AASHTO is not a government body, it does possess quasi-governmental powers in the sense that the organizations that supply its members customarily obey most AASHTO decisions.

AASHTO produces what's often called the "Green Book." Not to be confused with the Negro Motorist Green Book, AASHTO's Green Book is officially titled "A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets":

This manual sets standards like the width of auto lanes in roadways.

It makes sense that a lane should be wide enough to contain a car. And it makes sense that a lane should be wide enough to contain a semi truck. And given that this manual is primarily concerned with highways, then it makes sense that the lane should be wide enough so that all these vehicles can move at high speed and have some wiggle room so they won't accidentally bump into each other.

That all makes sense... until those same standards are applied to surface-level streets. As I was mentioned in a recent blog post on temporary curbs to be installed at Alameda Point, wider lanes encourage faster driving.

So implicitly, the AASHTO "Green Book" has been encouraging faster and unsafe driving within cities.

Candy colored guidebooks

To counter these implicitly auto-centric highway standards, NACTO was formed and produces its own guide books.

The NACTO Urban Street Design Guide is also green — but an avocado green:

The NACTO guide books are well illustrated and easy to skim. My kids occasionally take my set off the shelf and flip through them.

No need to buy them — you can also skim them and see the graphics online.

Here in Alameda, as of 2019, the NACTO are now the go-to source for design standards rather than the AASHTO Green Book:

Joining the club

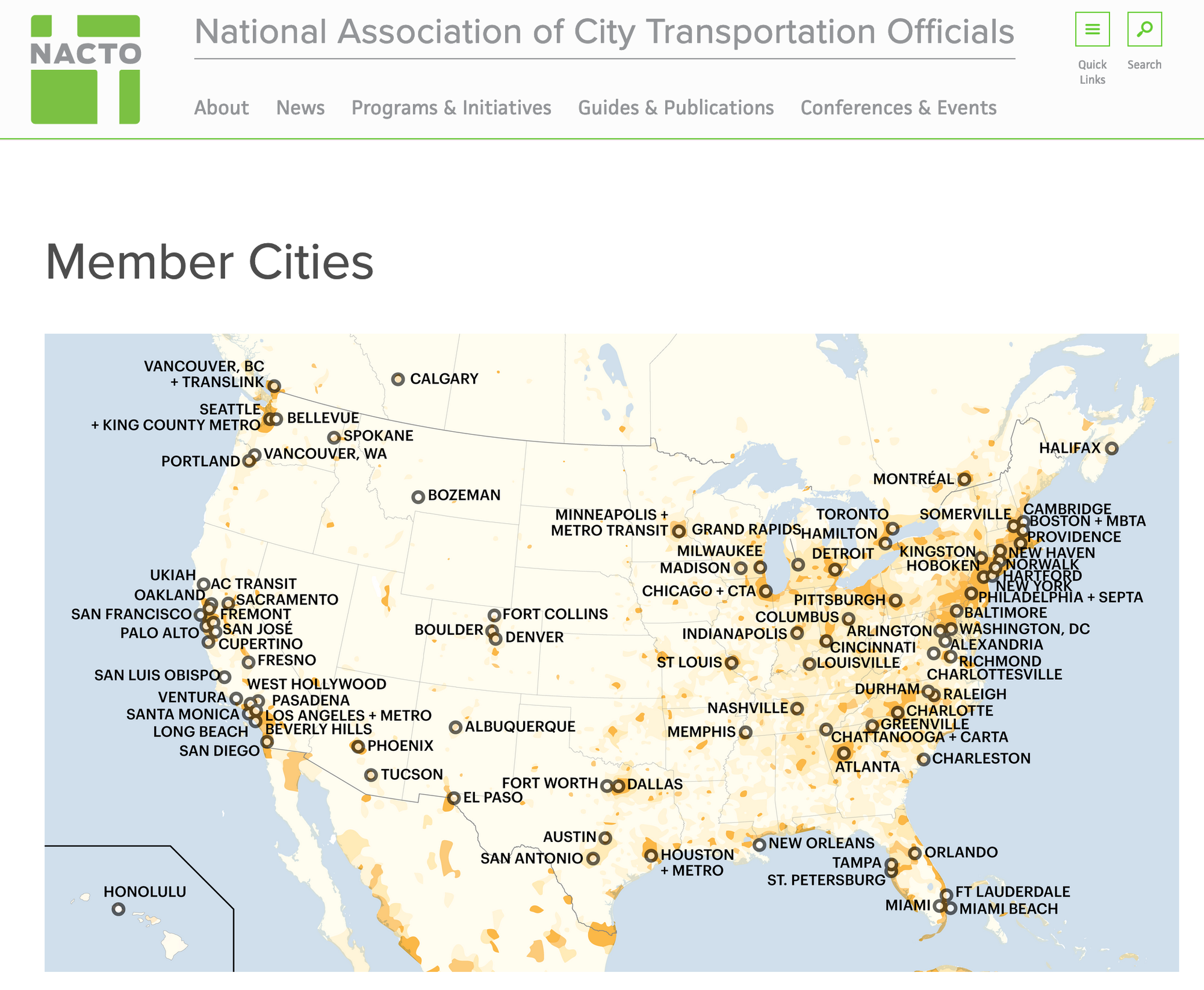

While the city has adopted the NACTO guides as policy, it doesn't look like has joined the membership of NACTO:

Joining the club and getting on this map could be beneficial to Alameda.

Alameda now has all the right local transportation policies for climate change and traffic safety — thanks to years of advocacy by residents and by staff members — but putting those policies into practice is still hard.

Putting those policies into practice is especially hard when it involves designs for physical streets. In some situations, it's a zero-sum situation, with engineers having to decide whether motorists or cyclists or pedestrians or delivery drivers will get priority for a given square foot of space. There are tradeoffs in all designs. More involvement in NACTO could give Alameda's staff more opportunities to learn from peer cities about how to best navigate these tradeoffs.

There are also tradeoffs in the overall methods of planning for street redesign projects. What is the right amount of public engagement to conduct for a project that will change the appearance and the behavior of a street? What methods of public engagement draw out useful feedback and encourage productive conversations? I've written previously about how I think Alameda is overdoing it with public engagement for some transportation "planning" projects (while also not realizing the value of some targeted public input on transportation "maintenance" projects) — but better than hearing from this from a rando blogger like me would be for city staffers to have more opportunities to discuss these sorts of challenges in private with their peers at other cities.

More involvement in NACTO could also make Alameda an even more attractive place to work on transportation. Hiring for the public-sector in the inner Bay Area is hard. I heard from city leaders that all the headlines about Alameda's first-in-the-Bay-Area compliant Housing Element drew a large number and range of applicants for the city's most recent land-use planning manage position. Professionals want to be a part of what's going on here (even if Alameda can't pay the salaries of neighboring cities, while still requiring the same high cost of living or long commute). Being similarly innovative on the transportation front could help to attract an even larger and wider pool of applicants the next time the Public Works or the Planning departments are hiring for transportation positions.

Don't get me wrong — Alameda's current transportation staff are skilled, and I also imagine they are already in touch with many local peers to discuss challenges and to share "best practices." Officially joining NACTO could just be another step forward in the evolution from the naively highway-centric past to a more thoughtful set of professional practices to plan and design streets for everyone here in Alameda.